For a musician, it must be a mixed blessing to get a gig as a bandleader on a late-night talk show.

On the plus side, it’s a sign you’ve made it. It’s a vote of confidence in your ability to lead, to improvise, and to pitch in the occasional witty banter. And of course, it’s a steady, lucrative job, in an industry where it’s rare to have either, never mind both.

But on the other hand, you stop being known as ‘you’ – instead, you are now ‘the band leader on that show’. It’s cynical but true to say that in accomplishing something great, you write the first line of your obituary. In other words, a musician who has struggled to make it as an artist in their own right risks being forever remembered as something they never really aspired to be.

And in some ways, the ‘leader’ part of ‘bandleader’ is a bit misleading; you’re not the leader of the show. That’s the host. You’re just the sidekick who plays for the studio audience during the commercial breaks.

However, late-night TV has changed a lot in the past decade. More and more, band leaders are involved in the shows in various ways. Jimmy Fallon uses The Roots in sketches and features, James Corden hired Reggie Watts specifically because of Watts’ background in comedy, and has said that he gives his bandleader “free range” to do whatever he wants on the show. Late-night band leaders are more like co-hosts than ever before.

This is a good thing for entertainment. It has helped to update a genre of show that began as a televised version of a radio show, and somehow stayed that way for decades. But the uncomfortable elephant in the late-night studio is the pattern clearly evident in the partnerships mentioned above: the host is white, the bandleader is black.

I often wonder what Jon Batiste’s thoughts were when he started as bandleader on Stephen Colbert’s show in 2015. He was the youngest person in history to be offered such a position. Was it a no-brainer? Or did he see it as a mixed blessing?

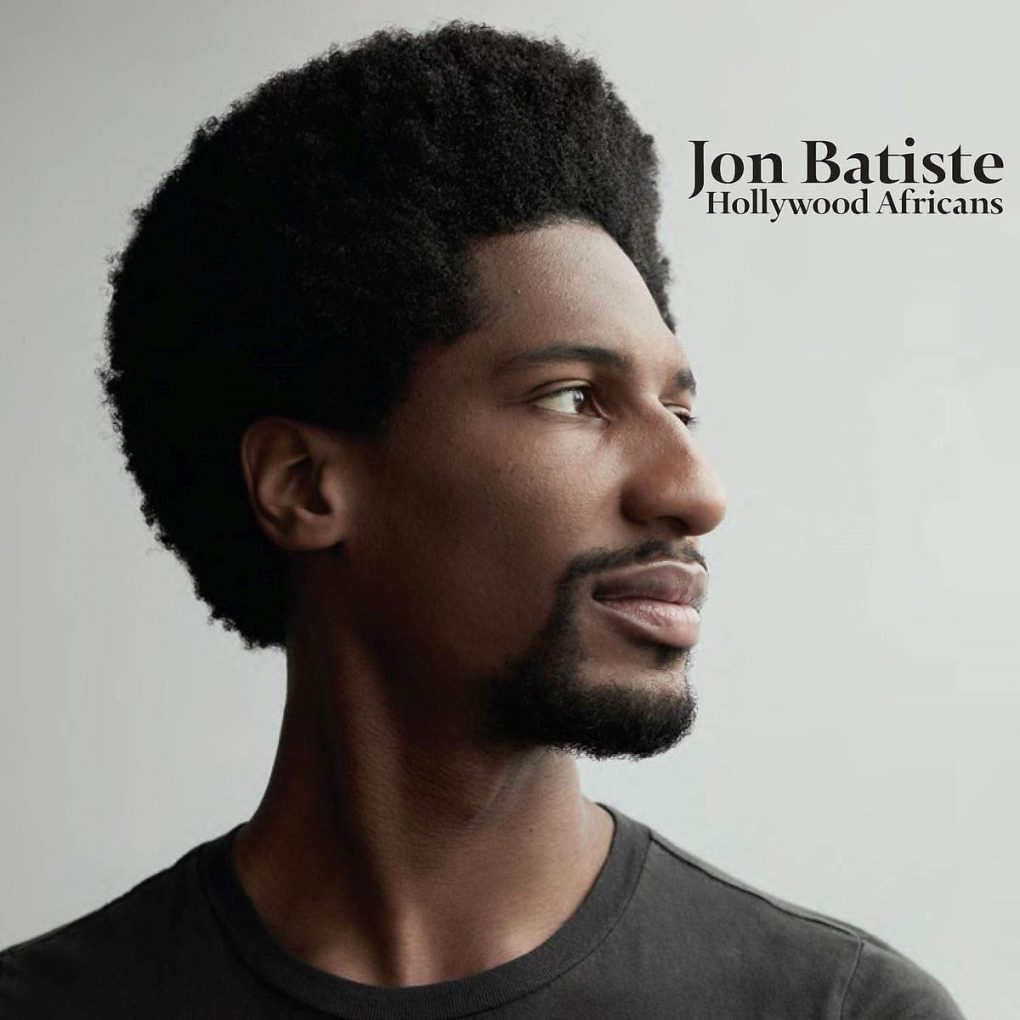

Batiste’s 2018 album, Hollywood Africans, is named after a Basquiat painting, which itself was a comment on the exploitative history of black people in American culture. But Batiste’s work feels less like a statement of protest, and more like a tribute to the musicians who have influenced over them, be they “Hollywood Africans” or…well, Chopin.

There is joy in Batiste’s album, but there is also heaviness. It’s a bittersweet sound that can only be created by someone who knows what it’s like to live a mixed blessing.

What makes this a beautiful song:

1. The opening dissonances, which almost sound haphazard, as if a cat were making its way across the keys. It just makes the eventual melody all the lovelier.

2. The way Batiste takes a Chopin nocturne and transfers its melody so easily to jazz. There must be something about Chopin’s genius that captivates modern musicians; we featured another Chopin re-work in week 75.

3. If the end sounds a bit abrupt, it’s because on the album it leads directly into a cover of Louis Armstrong’s “Saint James Infirmary Blues”. Making Chopin and Armstrong feel at home right next to each other is no small feat, and a credit to Batiste’s talent.

Recommended listening activity:

Putting a bandage on a really old scar.