When I was looking at a map of global penguin distribution, my first thought was, “why am I looking at a map of global penguin distribution?” But my second thought was, “the Galapagos Penguin shouldn’t exist.”

The Galapagos Penguin is a geographic oddity.

We tend to think of penguins as being exclusively cold-weather creatures, but the Galapagos Islands lie directly on the equator, with daytime temperatures regularly climbing into the high 30s (Celsius). Despite this, the plucky little Galapagos Penguin carries on, spending most of the daytime hours underwater, climbing out at night when the temperature drops.

But stranger than their adaptation to the equatorial climate is the fact that they’re there at all. The Galapagos Islands are about a thousand kilometres from the South American mainland, and the Galapagos Penguin is one of the smaller species; only about half a metre tall. It doesn’t seem possible that they should have had the ability to swim from the cost of Chile (where a related species exists) all the way to the tiny islands they now call home.

The prevailing theory is that they were carried there by a strong current called the Humboldt Current. I like this theory, mostly because it implies that at some point a group of South American penguins swam a bit too far from shore, were carried hundreds of kilometres by accident, and washed up on tiny hot islands inhabited by giant tortoises and, notably, no penguins. And yet, they survived.

So they’re not just an oddity; they’re the underrated, undersized underdogs of the penguin world.

Oh, and the next time someone tells you penguins only live in the Southern Hemisphere, you can let them know that parts of the Galapagos Islands poke into the world’s northern half, making the Galapagos Penguin the Northern Hemisphere’s only penguin species.

However, by the time you tell them that fact, they probably will have stopped listening, because people tend not to listen to folks who spend their time perusing maps of global penguin distribution.

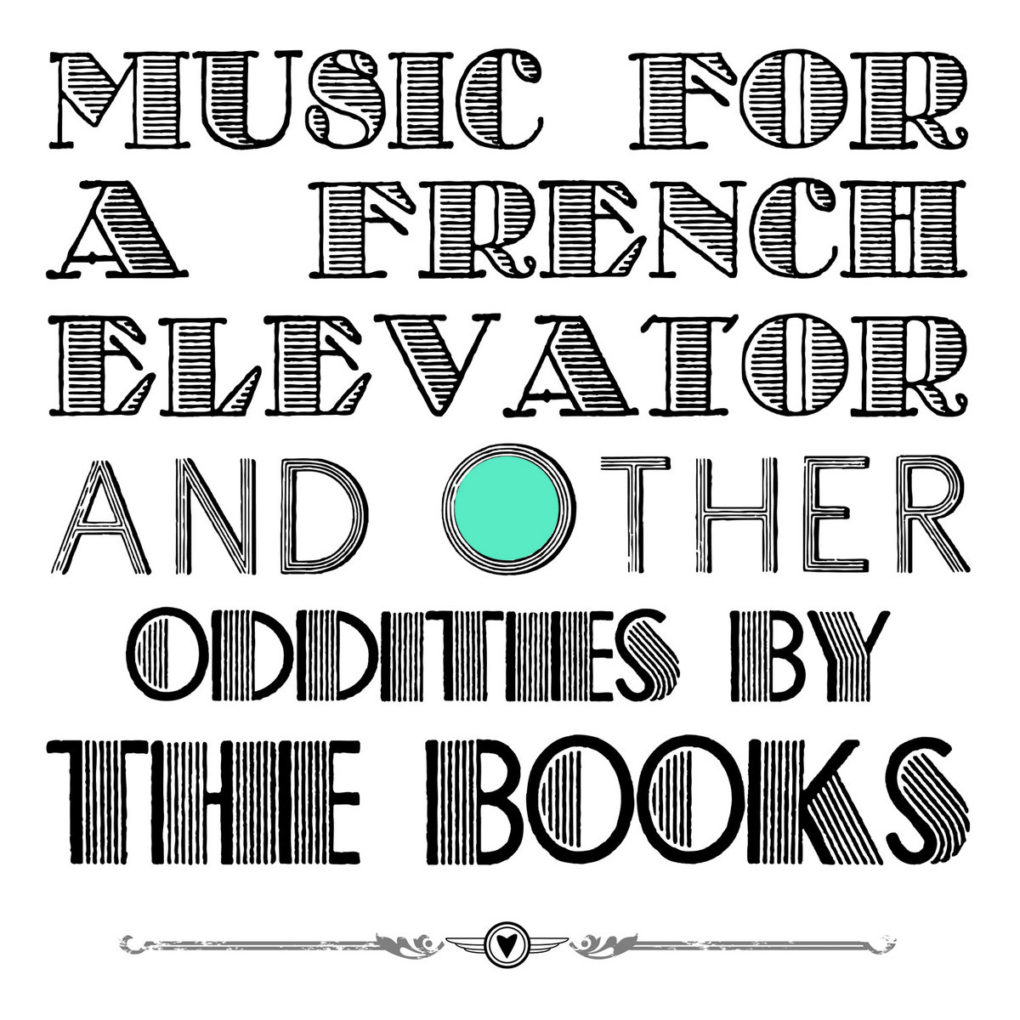

The Books, active mostly in the early 2000s, were as much of an oddity as the Galapagos Penguin. They built their own instruments, they used wacky vocal samples…Pitchfork called them a “genre of one.” Many of their songs were more like conceptual abstract weirdness than music. Listen to “Millions of Millions” from the same album as this track, to see what I mean. And yet, in the middle of a bizarre album with bizarre tracks like that, we get this beautiful little song.

What makes this a beautiful song:

1. The percussion that opens the track feels tropical and Antarctic at the same time.

2. The bass line, especially when played in plonk-plonk eighth notes, has a distinct waddle to it.

3. At 3:26, the secondary melody that had, up until this point, started just before the second of the bar, suddenly starts directly on that second beat. It’s a strange idiosyncrasy that messes with your internal metronome. However, the change corrects itself soon thereafter, heading back to the Southern Hemisphere where it belongs.

Recommended listening activity:

Wearing formal clothes for no reason.