Everything about the album Time Out is fascinating to me.

For starters, it was barely allowed to exist. Because of the experimental nature of its songs, the folks at Columbia records were sure it would be a commercial flop. So Columbia’s president, Goddard Lieberson, let them record it on the condition that they record an album of traditional songs first. This “eat-your-broccoli-and-then-you-can-have-dessert” approach ended up working brilliantly, as Time Out went on, despite initial negative reviews, to become one of the best-selling and most influential jazz albums of all time.

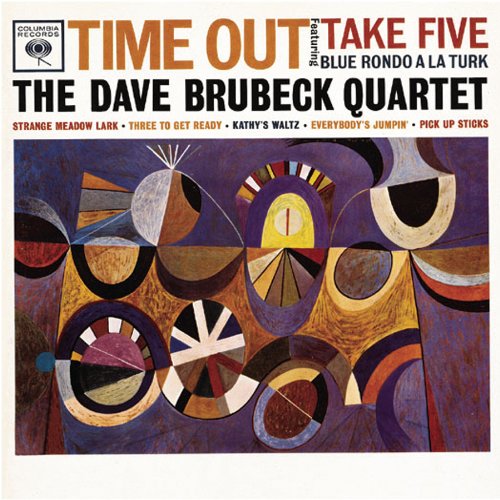

Then there’s the cover art. For some reason, I had always thought it was Picasso, but it turns out it’s by the Japanese-American designer Neil Fujita, who also designed a Mingus album cover, and book covers for novels like The Godfather and In Cold Blood. Fujita’s backstory is quite something: during World War II he was sent to the Heart Mountain Relocation Center, which was an internment camp where people of Japanese heritage could be safely kept away from American society, but still made available for the draft. Despite this unfairness, Fujita volunteered to fight in the war, made it out alive, and became one of the prominent American designers of the 20th Century.

But most fascinating, of course, is the music itself. There’s “Kathy’s Waltz” (named after Brubeck’s daughter, but misspelled on the album with a “K” instead of a “C”); there’s the legendary “Take Five” (the album’s biggest hit and also the only one not written by Brubeck); and then there’s this one, the forgotten little brother of “Take Five”, stuck on the album’s second side, but more than worthy of a listen.

What makes this a beautiful song:

1. The switching time signature. The album has many unusual time signatures, and in this song it alternates between 3/4 and 4/4. But like Time Out’s other songs, the unique counting isn’t done at the expense of a catchy melody.

2. The sax. Paul Desmond plays in such a soft, relaxed way that I like to imagine him playing this one in a comfy chair, with one arm slung over the headrest.

3. The ending. The piano creeps down chromatically for a while, and just when we’re sure we know how it’s going to end, crazy old Brubeck takes us up a few major thirds in a surprising melodic twist that sounds like the tone you might hear over the PA system in an airport before an announcement is made.

Recommended listening activity:

Stirring soup with one hand and snapping your fingers with the other.