A few weeks ago, I walked past a screen that was showing footage of that day’s Women’s March. I was wearing headphones at the time, listening to an Ella Fitzgerald song. Just then, a question popped into my head. It was so sudden that it almost felt like someone else was asking it:

“Can you name three female jazz musicians?”

I was about to list off Ella, Billie, Nina, and a whole roster of other legends, but the voice interrupted with a qualifier:

“No singers. Instrumentalists only, please.”

I stood there, staring at images of women all over the world, marching for gender equality, embarrassed by the simplicity of my question, and the implications of my inability to answer it.

The reason I couldn’t answer it, of course, is that since the earliest days of jazz, women have been underrepresented on every part of the stage other than behind the microphone. Any art form reflects the values of the culture that created it. At the time jazz was in its infancy, women were accepted as singers because the role of the singer fits with what we valued as ‘feminine’ – grace, elegance, beautiful to hear and to look at. Watching a woman sit at the drums, legs open, sweating through an intense drum solo…well, it wouldn’t have been imaginable.

But the thing about gender roles is that they are self-perpetuating. If one generation provides a certain type of role model, the next generation isn’t likely to stray from that template. So here we are, well into the second century of jazz, and there probably aren’t many more female trumpeters now than there were when Queen Victoria was on the throne.

It’s a complex problem, and this article is recommended if you’re looking for more depth on the matter. But for now, I take you back to the image of me, gazing dumbly at the Women’s March on a mall TV.

At the end of a long, brain-wracking moment, I could think of just one woman who made a career as a jazz instrumentalist, and that’s only because I’d featured her in a previous post. I decided further research, and much listening, was in my future.

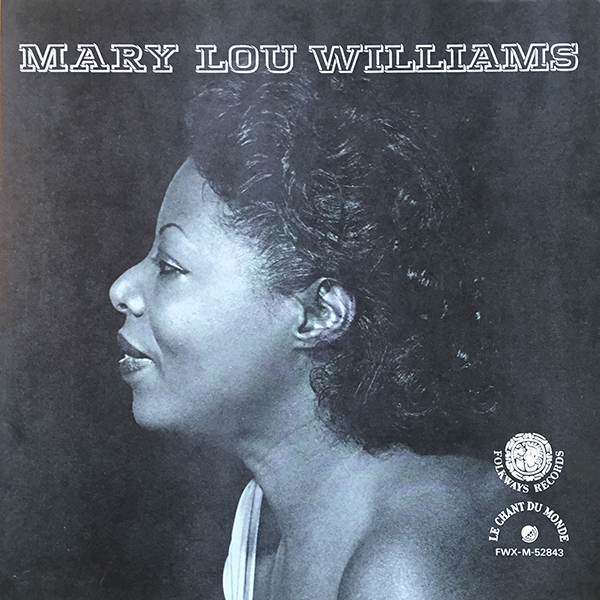

Granted, I’m only a casual jazz fan. Hardcore fans of the genre would be able to list many more than I was able to. But that’s the point. If casual fans know names like Monk, Parker, and Davis, they ought to know the name of the woman who taught all three of those men: Mary Lou Williams.

What makes this a beautiful song:

1. The uneasy chromaticism in the piano’s main melodic line. It reminds me of my own discomfort when I realized I was clueless about women in jazz.

2. The crunchy chords she intersperses between that awesome “doo-be-doo” bass line. Reminds me of Ahmad Jamal.

3. Williams’ version is instrumental, but in the original, from “Porgy and Bess,” the song describes one character’s doubts about the literal truth of the Bible. It’s about challenging the assumptions that you’ve never thought to question. About how we take certain things as truth, when in fact it might not be necessarily so.

Recommended listening activity:

Travelling in the opposite direction of the flow of traffic at rush hour.