A bit of a long post this week, but to compress this story any more than I already have would be to do it a disservice.

In the late 1990s, when this song was absolutely inescapable, I vaguely remember hearing that there was some kind of scandal, or controversy, or general kerfuffle, about copyright. They didn’t get proper clearance or something, and the Rolling Stones were suing them.

I didn’t pay much attention, primarily because it didn’t affect my enjoyment of the song, but also because this was the 1990s, when sample-based music was blossoming. A whole litigious mini-industry had sprung up whereby rights holders of songs that hadn’t sold a physical unit in a generation were cashing in by taking to court anyone who used as much as a snare-drum’s worth of their property.

Even though I was firmly on the side of the samplers, I do remember thinking that it was pretty bone-headed of The Verve to release a song that sampled The Rolling Stones without clearing it. I also remember thinking that is was pretty low of The Stones to sue for copyright infringement, when their entire catalogue basically a re-work of songs by blues artists from the southern US.

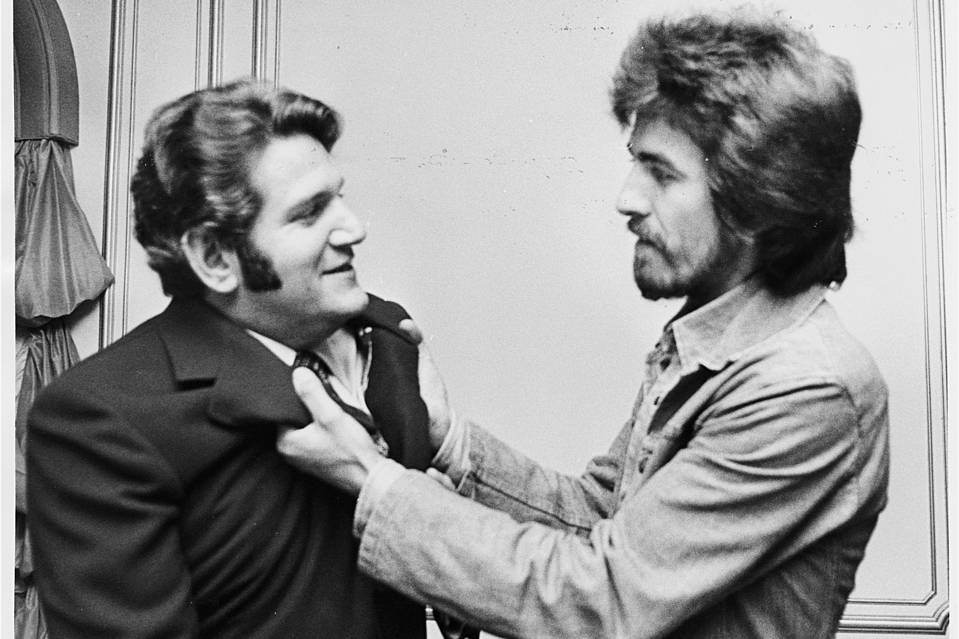

As it turns out, my assumptions about the situation were wrong on a few counts: The Verve did get permission, The Rolling Stones didn’t sue them, and neither party was the villain. That role goes to Allen Klein, a music producer with a bright mind for business and a dark, compassionless soul.

Well, perhaps I’m being a bit harsh. Klein may not have been a complete villain. In his early years, he was a champion for musicians, and among the first to recognize that bands were being exploited by labels and deserved more. He also saved The Beatles’ own label, Apple, from bankruptcy, and was a driving force behind the transformation of rock and roll in the 1960s.

On the other hand, I’m getting the information above from a recent book that was financed by Klein’s own son, so, you know, grain of salt and all that.

He probably wasn’t all bad, but it’s hard not to cast him as the villain when he fits the role so well. This is a man who, at one point, was managing The Beatles and The Rolling Stones simultaneously. Which feels like finding out that Coke and Pepsi are owned by the same person.

Paul McCartney hated him. George Harrison got sued by him in a story you have to read to believe. The Rolling Stones claim they weren’t fully aware of what they were signing when they gave Klein publishing rights to everything they had written up to 1971…and that’s where “Bitter Sweet Symphony” comes in.

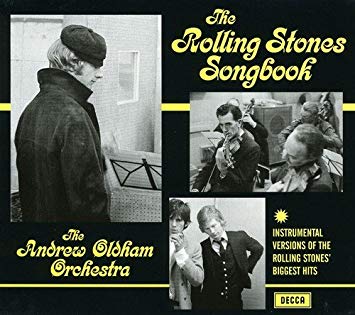

The string section snippet that The Verve used for their mega-hit was from a Rolling Stones song…kind of. It was actually from Andrew Oldham’s 1966 symphonic version of their song, “The Last Time” – a version that sounds vastly different from the original; different instrumentation, different tempo, no lyrics. It’s really not the work of the Rolling Stones at all.

The Verve did seek permission for the use of Oldham’s track. What they didn’t do – or at least, didn’t do right up until “Bitter Sweet Symphony” was ready to be released – was to get copyright clearance for the original Rolling Stones composition, despite the fact that it bore little to no resemblance to The Verve’s song.

When approached by The Verve’s record label, Allen Klein stated that he “didn’t believe” in sampling, and refused clearance. Which was brilliant: he knew the label couldn’t release The Verve’s album without its lead single, and that they would leave the meeting crapping their pants. Klein then called them back and gave them an offer. Klein’s publishing company, he said, would enjoy 100% of the royalties generated by “Bitter Sweet Symphony,” and Verve singer/songwriter Richard Ashcroft would receive a one-time payment of $1000.

And so, this story really does have an appropriately bittersweet ending for Richard Ashcroft and The Verve:

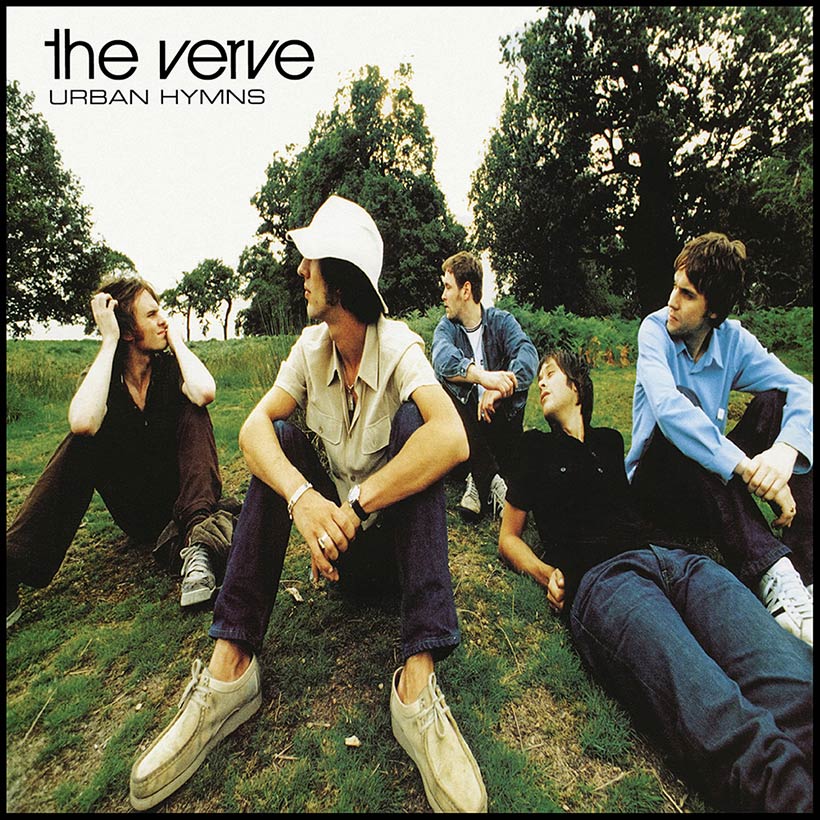

- Sweet: they got to release their album, Urban Hymns, which was widely praised by critics, sold like crazy and made them lots of money.

- Bitter: they never saw any of the money for “Bitter Sweet Symphony,” including the enormous sums it made through licensing for companies like Nike.

The biggest irony of all is that the original version of “The Last Time” – not the symphonic one, but the straight-forward one that Allen Klein owned the rights to – was itself clearly a rip-off of a song by The Staples Singers.

If only Allen Klein had owned the rights to The Staples Singers’ catalogue, he might have been able to sue himself, perhaps tying himself up in a legal battle so complicated that he wouldn’t have had time to rain on The Verve’s parade.

What makes this a beautiful song:

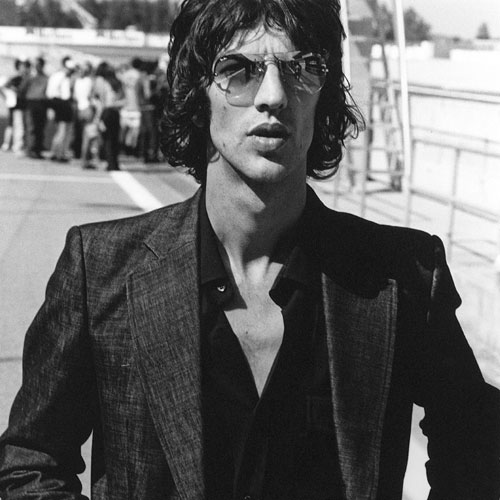

1. From all the interviews I’ve seen with Richard Ashcroft, he couldn’t care less about songwriting credit or royalties. The lyrics seem to reflect this attitude, with all their mentions of not needing to change, not wanting to be a slave to money, letting the melody shine.

2. The video, which I also remember from its original release, was a real shift at the time. One long shot of Ashcroft walking the streets of London, either not noticing or not caring about anyone who might get in his way.

3. It just sounds so victorious. Normally, I dislike it when songs don’t have a bridge, or a b-section, or some kind of change in chord structure that makes the listener want the chorus to come back. But in this one, I don’t care. I could just play it all day, close my eyes and imagine I’m walking down a street somewhere, sporting a scruffy Brit-pop haircut and obliviously knocking the ghost of Allen Klein to the pavement.

Recommended listening activity:

Replaying, in your mind, a confrontation you had years ago, but this time you say what you should have said, and walk away like a champion.