One of Camille Saint-Saens’ best-loved works is his 1886 suite, The Carnival of the Animals. It is at times playful, at times beautiful, and it makes a great children’s entry point into classical music, along with classics like Prokoviev’s Peter and the Wolf and Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker.

It’s a classic.

Oh, and Saint-Saens specifically instructed that it should not be published until after his death.

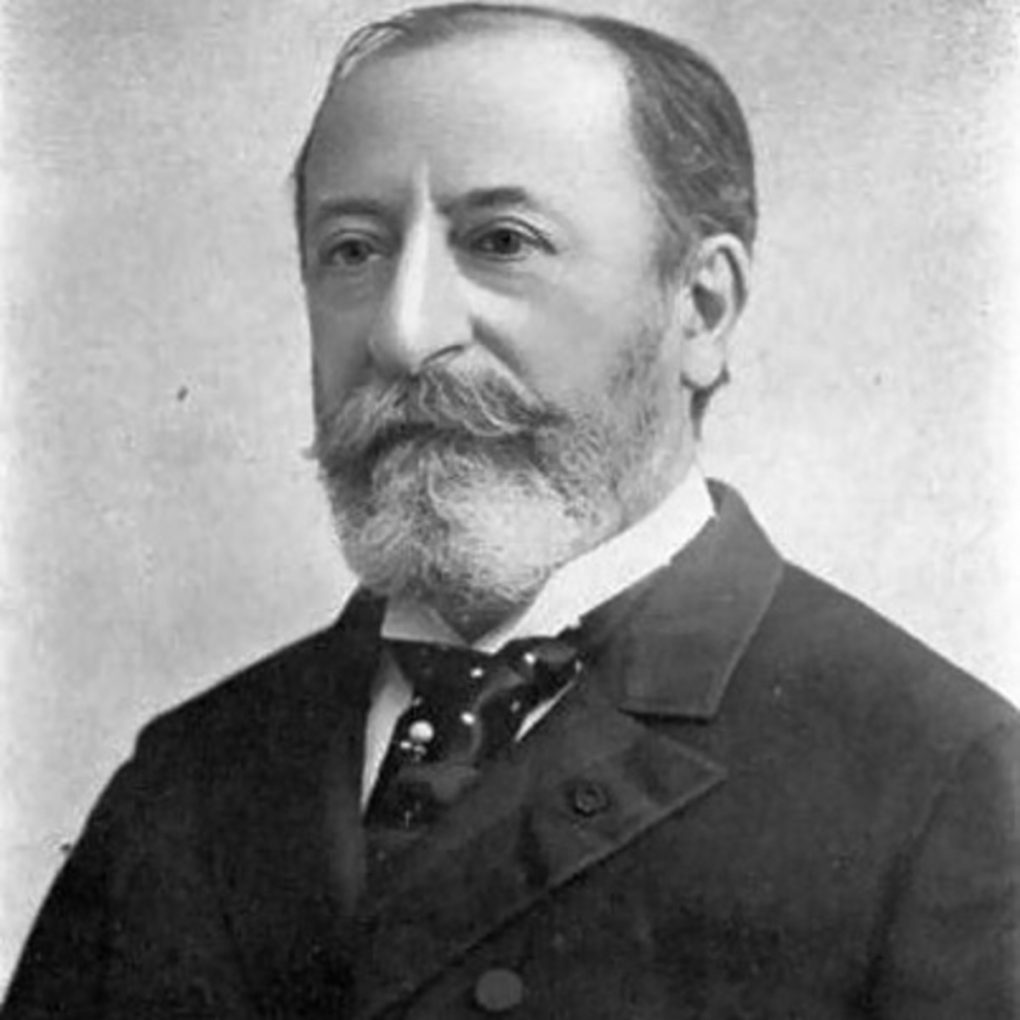

The story is that during a year-long concert tour of Germany beginning in 1885, Saint-Saens had made some harsh criticisms of Richard Wagner’s work. This was a bit like going to the sun and criticizing heat. It caused significant backlash in Germany, sparked protests at some of his concerts, and lost him a bunch of engagements.

The tour ended, Saint-Saens was disheartened, and left his Paris home to find peace at a cottage in the Austrian countryside. While there, he began work on The Carnival of Animals.

Correspondence with his publishers in Paris indicate that although he knew he should be working on his Third Symphony, he couldn’t help going back to The Carnival, because it was “just such fun.”

Each movement is named for an animal. Many are less than a minute in length, and the whole 14-movement suite clocks in at under half an hour. He quotes other composers’ melodies constantly, like in “Tortoises” when he takes Offenbach’s famous “can-can” melody and slows it down to the pace of, well, a tortoise.

There’s another tongue-in-cheek moment when the orchestra is clearly mimicking the sound of donkeys, but rather than calling that movement “donkeys,” Saint-Saens gives it the vaguer title, “personages with long ears” – a title most people take to be a shot at music critics.

Despite how much he enjoyed composing The Carnival, Saint-Saens refused to publish it while he was still alive, apparently worried that it would damage his reputation as a “serious” composer. Only a select few heard it, at private performances, during Saint-Saens’ life, including close friend Franz Liszt.

It makes me a bit sad to think that Saint-Saens didn’t feel free to share something he’d obviously enjoyed creating. After the train wreck that was his 1885 tour of Germany, I think it would have been bold to publish something frivolous and fun. Like a candy-coated way to tell his critics where to go.

There was one exception, however. One movement that Saint-Saens agreed to have published in 1887: this movement, The Swan.

What makes this a beautiful song:

1. It has to be one of the best pieces for cello in the history of cello. And as we know, nothing beats a good cello.

2. The cello is backed up by two pianos, but they’re employed so subtly that it’s not immediately apparent that there are two of them. One supplies some gentle arpeggios, while the other sprinkles the occasional fairy dust in the form of quietly rolled chords high up the keyboard.

3. It’s the second-to-last movement in a suite of fun and silliness, so its beauty completely ambushes the listener. That’s kind of a genius move. I don’t think Saint-Saens needed to worry about his reputation; only a “serious” composer can pull that off.

Recommended listening activity:

Taking your hobby a bit more seriously.