It is 1830. Industrialization is in full swing. Labourers, made redundant by advances in agricultural technology, are flocking to London to find factory work.

The city – dirty, dangerous, and disconnected from nature – is a pretty awful place. Those who can afford to find refuge in some of the world’s first suburbs; neighbourhoods on the outskirts of London that attempt to combine the natural serenity of the countryside with convenient proximity to the life of the city.

Conditions are perfect for inventor Edwin Budding, whose 1830 masterpiece will become a symbol of suburbia for generations to come: the lawn mower. Specifically, he invents the cylinder lawn mower, a design so effective and easy to use that versions of it are still widely available today.

The zoological gardens at Regent’s Park in London are among the first to purchase the invention from Budding, and they are pleased to discover that it can allow one man to do as much cutting in an hour as several men could do with scythes, and much more accurately. Soon, all members of Britain’s upper crust are in possession of lawn mowers so that they (or at least, their groundskeepers) can keep the lawns uniformly shorn.

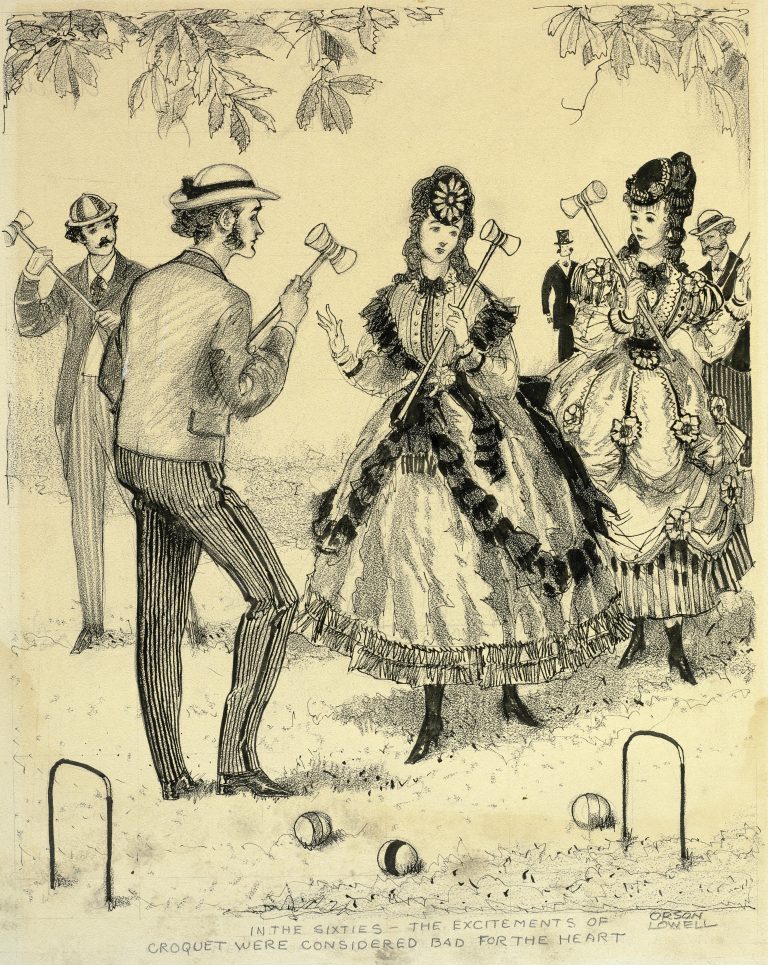

Before long, the cylinder lawn mower was ready to make lawns perfect for the pastime that was about to become all the rage among said upper crust: croquet.

Although similar games were played in medieval France, the first recorded game of croquet was played in the 1860s. Within a few years it was THE pastime in Britain, as well as France and much of the western world. The All England Club at Wimbledon was in fact originally a croquet club. I can just imagine the sight (and distinctive sound) of the groundskeepers at Wimbledon preparing the grass for an afternoon’s croquet.

As the century ended, croquet’s popularity peaked. After its one and only appearance in the Olympics (at the Paris games in 1900) croquet’s following fell off sharply. Ground space at Wimbledon was given over to the new popular sport of lawn tennis, and although the word “croquet” still hangs on in the official title of the All England Club, croquet is more past than pastime today.

One other visible relic of the sport is the London street known as Pall Mall, which was once home to a croquet field and which takes its name from the French word for croquet, “paille maille,” or “ball and mallet.”

All this is to say that I’m glad that Jeremy Villecourt, a Paris-based musician on a London-based label, chose the stage name Croquet Club for his musical project.

What makes this a beautiful song:

1. The piano sample is from “Clair de Lune,” featured on this blog in week 29 and composed by Claude Debussy, whose life (1862-1918) overlaps almost perfectly with croquet’s rise and decline.

2. Rather than a snare drum, Villecourt chose a rim hit for the percussion. When listening to that sound, it’s hard not to imagine a croquet mallet hitting a ball.

3. The vibe is pretty laid back until the halfway point, when the vocal sample enters, repeating the line “you left me” – and suddenly the mood turns nostalgic.

Recommended listening activity:

Scouting out places in your neighbourhood where you can play this summer.