In keeping with the title of this song, I wanted to tell you a “lost at sea” story this week. The problem is that most “lost at sea” stories are pretty grim. They usually end in death, and even when they end with a rescue there’s often a dark angle to the story – cannibalism, for example – that pushes the story’s themes more towards desperation than resilience.

But there is one shipwreck story that will leave you with some faith in humanity.

In 1965, six teenagers at a Catholic boarding school in Tonga were plotting an escape. The school was, for them, barely better than a prison. They gathered a few supplies, stole a boat from a grumpy old fisherman nobody liked, and hoped to set sail for Fiji under the cover of night.

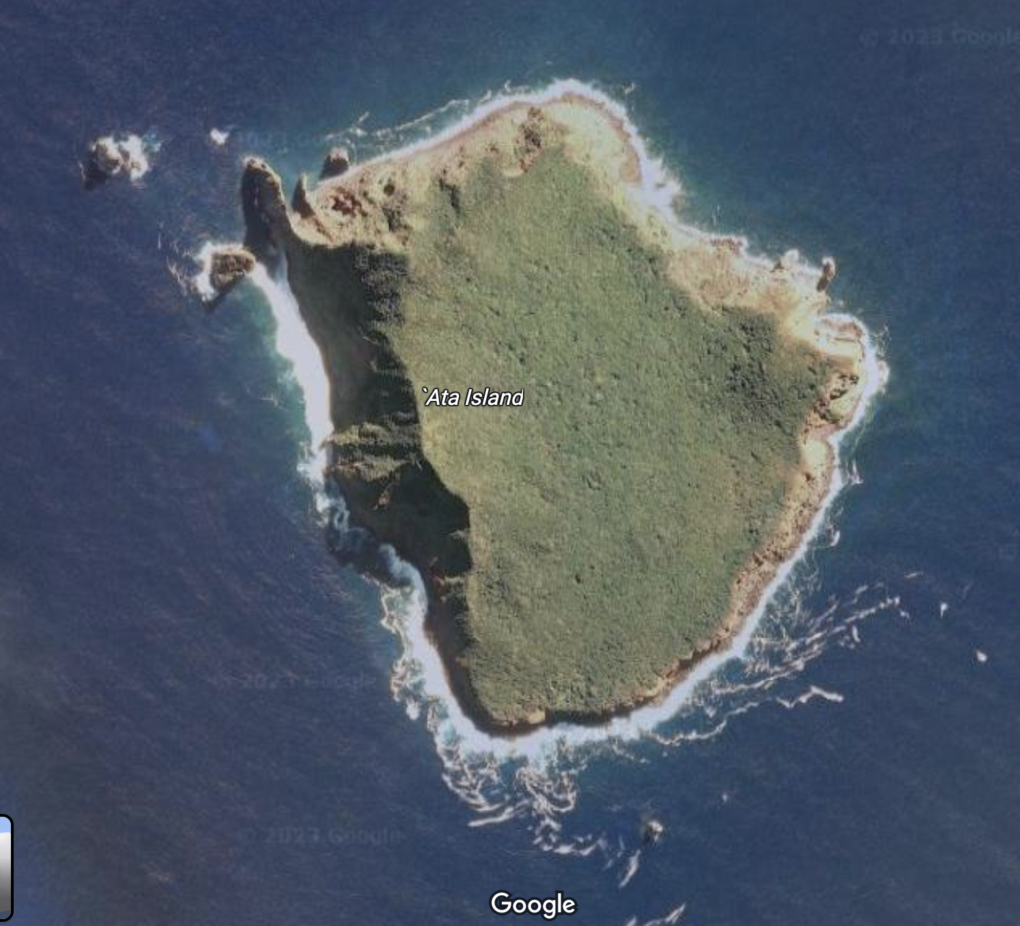

They were barely underway when a storm pushed them off course, snapped the boat’s rudder, and left them at the mercy of the ocean currents. After drifting for a week with only two days’ worth of food and water, and with their boat falling to pieces, they finally sighted land, but it wasn’t Fiji. It was a mountainous and uninhabited island called ‘Ata, about 320km southwest of their starting point.

Surviving on this island would be nearly impossible for most people, but the six Tongan boys managed it. They caught birds with their bare hands, collected rain water, built shelters, and prayed that someone would sail near enough to the island to see them. They were doing okay. They even made a guitar and a badminton court to pass the time.

While exploring the island’s highest point they discovered the remnants of a village. The island’s original inhabitants had been forcibly removed by Peruvian slave traders nearly a century earlier, but some of their tools and vegetable gardens and even feral chickens remained. With these, the boys began farming.

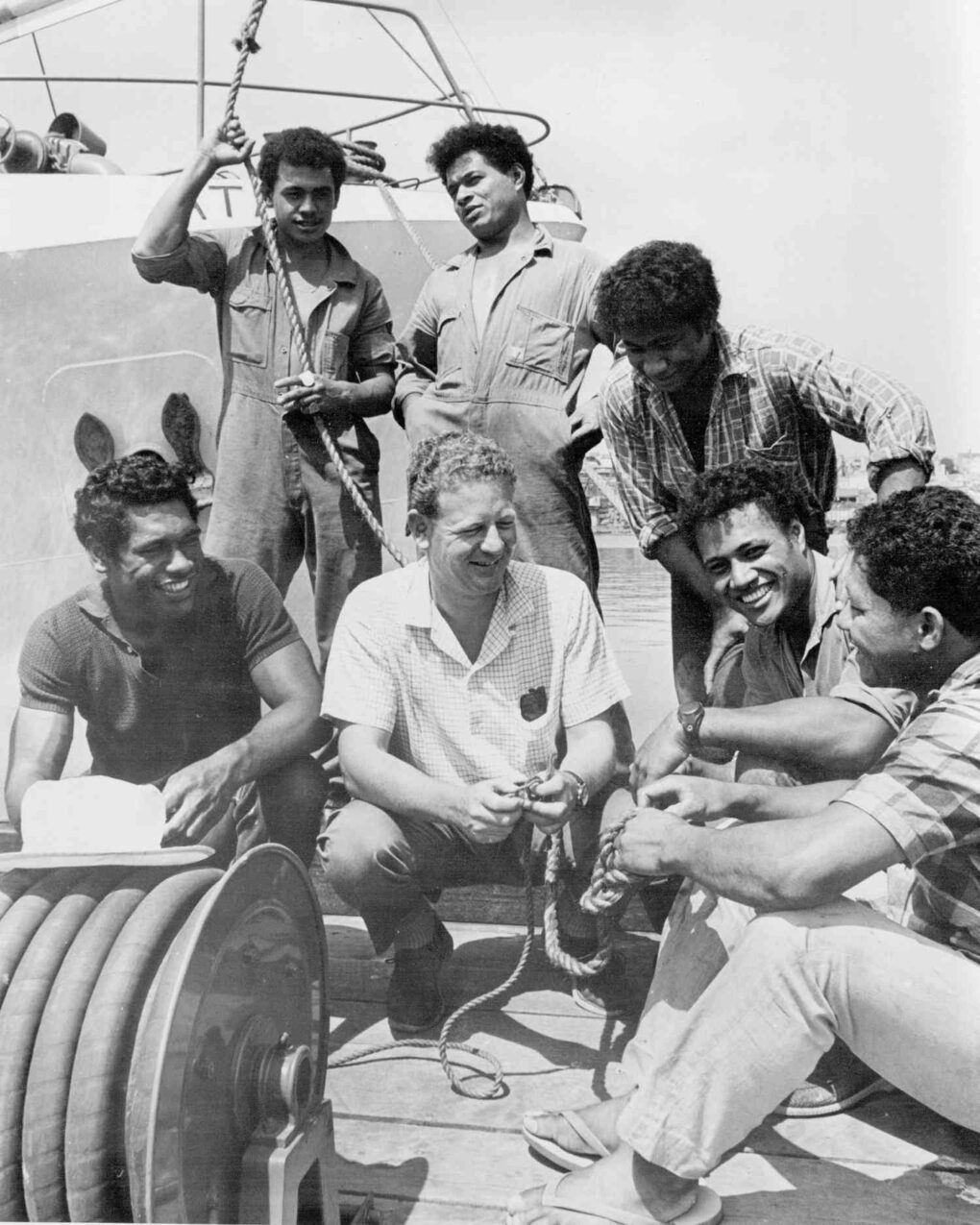

In September 1966, 15 months after drifting away from Tonga, they were spotted by Peter Warner and his crew as they were testing some fishing equipment just offshore.

Now let’s pause here for a minute, because Peter Warner shouldn’t have been at sea in September 1966. He should have been a lawyer in Australia, or perhaps taking over the electronics company his father had founded forty years earlier.

But Peter had never wanted to be part of the wealth that had given him such a comfortable upbringing in Melbourne. At 17, he ran away from home to pursue his dream: sailing. A year later he returned, and his father made him finish high school and enroll in the law program at the University of Melbourne.

Six weeks into the school year, he ran away again, and this time didn’t return for three years. He served in the Swedish navy and even learned Swedish so he could write the sailing exams needed to earn official certification.

Still, sailing wasn’t going to make him a living, and through his young adulthood Peter reluctantly worked in accounting at his father’s company, only getting out onto the open ocean when his schedule would allow it.

And so, there he was, just off the shore of ‘Ata island, when he saw evidence of fire on the hillside. Knowing that wildfires were extremely unlikely, he brought the ship closer, until they heard the sound of voices, and eventually the six young men who had survived more than a year on the remote island.

It’s fitting that the boys, driven to the sea by the prison-like Catholic boarding school that they so hated, were rescued by someone who was driven to the sea to escape the prison-like expectations of his father. They returned to Tonga, where funerals had long since been held to mourn the six boys, and fell into the grateful arms of their parents.

Except: remember the grumpy fisherman whose boat they stole? His heart was unmoved by their story of survival, and so, having barely set foot back at home, the castaways were arrested for stealing the man’s boat and promptly thrown in prison.

When news of this reached Peter Warner, he arranged to shoot a documentary about the boys’ survival with the help of an Australian news channel. He then used the money from that contract with the station to repay the grumpy old fisherman for his boat. The boys were finally free.

So there you have it: a lost-at-sea story that doesn’t destroy my faith in humanity. Although I have to say that it doesn’t exactly build my faith in authority figures.

What makes this a beautiful song:

1. The tight harmonies of The O’Pears make me think of the Tongan survivors’ collaboration.

2. The swaying 3/4 time signature makes me think of ocean waves.

3. As the very last chord fades, a seagull calls out. Just to remind you that land is nearby.

Recommended listening activity:

Planning an escape. Or a rescue.